There are a lot of valid critiques of Western gender norms and the ideologies which venerate binarism and “traditional” sex roles. Many have taken to science fiction to air these critiques in various formats and frames. What Benjamin Rosenbaum asks with his book The Unraveling, is what if you had all that gender critique and a bag of cyberpunk/body-modding/deep future craziness chips?

I read this book in preparation for the 2025 NarraScope conference, where the author will be speaking on his work in ChoiceScript development. Sidebar: if you’re interested in the topics this blog discusses, why not NarraScope? I consider it the premiere North American game design conference for people who aren’t absolute buffoons of capital 🙂 You can even attend via Discord without leaving the comfort of home.

Okay, so The Unraveling is about a youth named Fift Brulio Iraxis who lives on a planet far from Earth many centuries in the future. Fift and everyone else on this planet possesses multiple bodies all inhabited at once. Strict norms about conduct and gender roles rule Fift’s society, and Fift’s own ability to conform to zir gender of Staid is in question. This is risky not only for Fift but also for zir’s sprawling cohort of parents. Everyone lives under constant peer-to-peer surveillance through an internet connection embedded in all their heads.

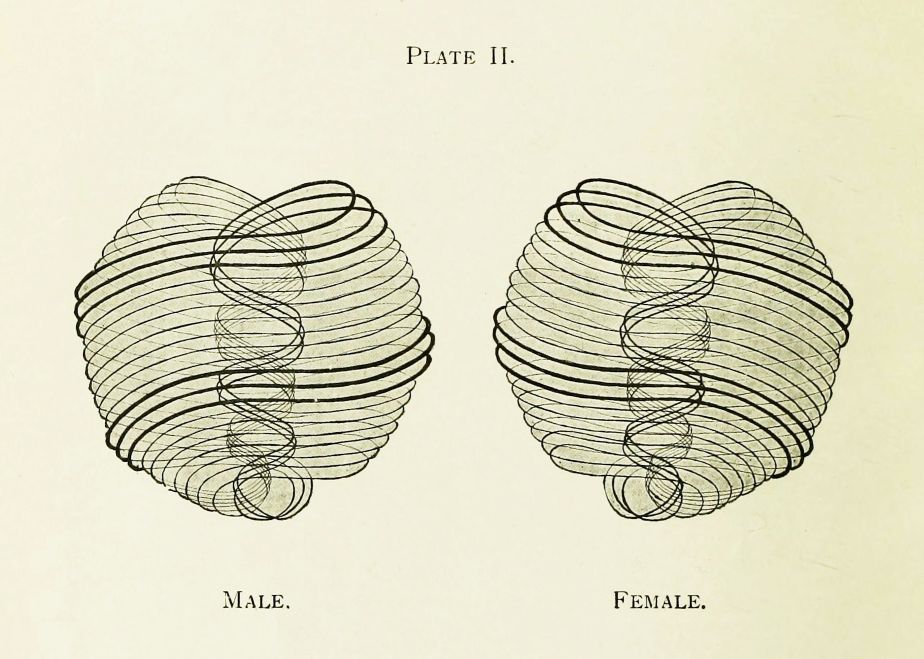

Like all effective utopian/dystopian literature, The Unraveling uses its exaggerated setting to confront the troubles of our world. The genders of Fift’s world, Staid and Vail, have no relation with genitals or reproductive role, both of which are completely malleable thanks to tremendously advanced body modding technology. Instead, these two genders oppose each other along a binary of emotional expression: the Staids are meant to be constantly serious, scholarly, and rational, while the Vails are assumed to be perpetually rash, lively, and libidinous. If these sound like arbitrary divisions that no one could possibly live up to every minute of every day, congratulations: you are soooo close to a big realization about gender in general. The Unraveling succeeds in thoroughly defamiliarizing the reader with the ideas it deconstructs without having to constantly double-back to reference real world Western gender norms. It makes no sense to divide the world between Staids and Vails, and I, a reader who had no meaning to assign to the words “Staid” and “Vail” until beginning to read this book, can easily see how silly this division is. And with that lingering thought in my head, I might wonder if it really makes that much sense to fervently divide the world into “men” and “women”, when those categories becomes incoherent under even cursory inspection.

This clarity of intention does not make The Unraveling necessarily an easy read. Rosenbaum unloads a truckload of new future terms to describe Fift’s society and all it contains. The protagonist’s multiple bodies force the interweaving of two or three different conversations, locations, and streams of thought during many pivotal scenes. This painstaking engagement with the minutiae of unusual consciousnesses and impossible technology reminded me sharply of Vernor Vinge’s A Fire Upon the Deep (a high compliment since that book also rocks).

Not only can Fift’s POV shift between three different bodies, but ze can also look in on any other citizen using the distributed surveillance technology which has ossified their society into stultifying dullness. Though the world of The Unraveling is free of many of the miseries we face today (war, disease, premature death, etc.), Rosenbaum is wise enough to see that any seeming utopia will have citizens who find themselves unsatisfied with the structures that keep the peace. Rule through consensus maintains a large core group of somewhat-satisfied, somewhat-bored people who spend all their time chasing approval from viewers in order to achieve a modicum of success, and that leaves people who fail to conform on the margins of society, viewed only pruriently and disapprovingly. And while the misfits of Rosenbaum’s world are not starving, like they often are in ours, they’re also not free to live full lives. Lampooning the practices of a society dependent on surveillance and consensus ratings from peers without slipping into the goofy anti-cancel-culture dingusery of contemporary right-wing SF isn’t easy, but Rosenbaum succeeds because of his expansive compassion for all the characters.

At the heart of The Unraveling is the romantic friendship of Fift and zir classmate, a Vail-gendered person named Shria. Young people in the world of The Unraveling are expected to mix only with those of their same gender and never with others, and as Fift and Shria grow closer, they push the limits of what their society will allow. Because they happen to live in a time of growing discontent, their taboo-breaking catapults them into celebrity/symbol status. I will admit I didn’t always find the Fift/Shria relationship compelling, but I also think Rosenbaum knew some readers might feel this way because he tweaks the skeptics near the book’s end with the inclusion of humorous in-universe shipping discourse. More than anything else, the connection between Fift and Shria is an engine to fuel questions about why the world they inhabit is so rigid and whether that rigidity truly benefits anyone.

I think I was also perhaps unsatisfied with the emotional depth of Fift and Shria’s relationship because Rosenbaum draws some of Fift’s other relationships with such poignancy. Fift’s relationships with zir numerous parents moved me profoundly. Each parent loves and care for Fift in their own way, and yet is deeply imperfect and wounded by the pressures of their intrusive and controlling society. In each of Fift’s parents I saw some failings of my own family members and myself, and in the text’s affirmation of their sincere love I was reminded of the constant tension between our love for others and our infinite capacity to fail them. Though society at large castigates Fift and zir family, and zir parents castigate themselves for raising such an abnormal child, Fift’s slow-growing bravery and conviction testifies to the best of zir parents’ efforts in raising zir.

I read some reviews of this book which complained about the ending: its abruptness and lack of resolution. But this is a key part of the viewpoint Rosenbaum advances. Fift was never going to be able to change the belief systems of a whole world, not with Shria’s help or anyone else’s. Ze was only one small part of a big wave of change and confusion, a societal Unraveling. The book leaves Fift as a young adult, with zir own life and future. It is not the future zir parents planned for zir, nor is it the future society insisted ze desire. It isn’t perfect. But it has its own unique satisfactions because Fift chose it. This is a good way to look at one’s own gender expression–it may not be what people are expecting or what they believe is right, but if you chose it and created it and feel comfortable in it, then it’s right for you. Fift doesn’t lead a gender revolution that changes the whole of zir society. But ze creates a small space for zirself and zir friends to thrive, and ze does so not by inventing new different additional colors of straitjacket for everyone to wear, but by genuinely enforcing the rule of “wear what you want”. In time, the space Fift built might grow to encompass the world, as the Ages pass.